Concurrency

What is it?

Concurrency is the characteristic of a program whereby different parts (or units) of the program can be executed out-of-order or at the same time without affecting the final outcome.

- this differs from Parallelism, which is the ability to run 2 things at the same time (e.g. what happens on a multi-core processor).

- concurrency is one way to achieve parallelism, though parallelism is not the only goal of concurrency. Put another way, a concurrent program is one that can be parallelized.

A concurrent system is one where the processes know how to wait their turn to access resources.

Why?

One thing you never want in computing is for 2 different programs to be accessing/writing to the same memory location at the same time. This results in file corruption.

- ex. This could result if 2 different programs are trying to write the same file at the same time.

- for this reason, Operating systems and programming languages provide various mechanisms to coordinate access to shared memory between different programs or threads. These mechanisms include locks, semaphores, mutexes, and other synchronization primitives.

With a concurrent system, we aren't going to concern ourselves with what is happening at the CPU level and whether something is running on multiple cores or not. Instead, we allow the runtime (e.g. Go runtime) and OS to take care of it.

Bugs arising from concurrency issues are hard to find by testing, because such bugs are only triggered when you get unlucky with the timing.

It may seem that two operations should be called concurrent if they occur “at the same time”— but in fact, it is not important whether they literally overlap in time. Because of problems with clocks in distributed systems, it is actually quite difficult to tell whether two things happened at exactly the same time.

- For defining concurrency, exact time doesn’t matter: we simply call two operations concurrent if they are running independently and are both unaware of each other, regardless of the physical time at which they occurred.

- that is, we say that two processes running on a computer system that are executing independently of each other and are not sharing any data or resources, are concurrent.

Resource Starvation

Resource starvation occurs in concurrent computing where a process is denied access to resources that it needs to process its work

When starvation is impossible in a concurrent algorithm, the algorithm is called starvation-free

- aka lockout-freed, or said to have finite bypass

Liveness

Liveness is the quality of a concurrent algorithm where multiple processes may have to "take turns" during the critical sections in order to continue to make progress. In this way, the program does not stall, and progress can still be made.

Liveness guarantees are important properties in operating systems and distributed systems

Critical Section

The parts of a program where a shared resource is being accessed needs to be protected in a way that will prevent concurrent access from being possible. This protected section is called the critical section, and it cannot be executed by more than one process at a time.

- anal: think of the critical section as the traffic cop at the sensitive areas. It allows each process to know when it's their turn to access the data.

Typically, the critical section accesses a shared resource, such as a data structure, a peripheral device, or a network connection, that would not operate correctly in the context of multiple concurrent accesses.

A critical section is typically used when a multi-threaded program must update multiple related variables without a separate thread making conflicting changes to that data. In other words, each thread knows to wait its turn before manipulating and accessing the data.

Whoever holds the lock is the process that is allowed to access the resource (ie. it's their turn)

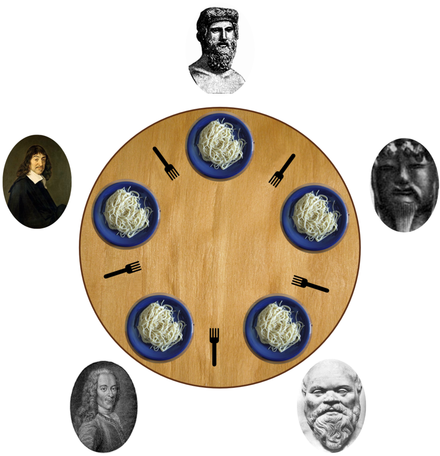

Dining Philosophers Problem

The dining philosophers is an analogy for a program where the processses must alternate between one task and another (here, eating and thinking)

The problem was designed to illustrate the challenges of avoiding deadlock, a system state in which no progress is possible

How it works

The philosopher is either in thinking or eating state.

- eating -> the philosopher has both forks in his hand

- thinking -> everything else

The goal is to create a program that would result in no philosopher having starved. This would be the case if the program were to deadlock because the line of execution was stalled.

- if we are able to achieve this, then we will have created a concurrent algorithm

A philosopher having starved represents resource starvation

Once the philosopher has finished their meal, they place down both forks so that they are available to others.

There are different approaches to solving the dining philosopher's problem

- Introduce a waiter who enforces that only one philosopher at a time may pick up 1 or 2 forks, meaning that the philosophers have to request and receive permission from the waiter before picking up the fork. This results in a system where only one philosopher at a time can pick up a fork.

The word consistency is overloaded:

- It can refer to replica consistency and the issue of eventual consistency that arises in asynchronously replicated systems (ie. replication lag).

- It can refer to consistent hashing, which is an approach to partitioning that some systems use for rebalancing.

- In the CAP theorem CAP Theorem, the word consistency is used to mean linearizability.

- In the context of ACID, consistency refers to an application-specific notion of the database being in a “good state".

Children

Backlinks