Closures

A closure is created when a function is defined inside another function, and the inner function has access to the variables of the outer function even after the outer function has finished execution and has returned.

- recall that functions return as soon as the body code is executed.

A closure is an expression (most commonly, a function) that can have free variables together with an environment that binds those variables (that "closes" the expression).

function outer() {

const outerVar = 'I am from outer';

function inner() {

console.log(outerVar);

}

return inner;

}

const closureFunction = outer();

closureFunction(); // Outputs: "I am from outer"

Since a nested function is a closure, this means that a nested function can "inherit" the arguments and variables of its containing function. In other words, the inner function contains the scope of the outer function.

When a variable is "captured" by a closure, it means that the inner function (the closure) maintains access to that variable even after the outer function in which the variable was originally defined has finished executing.

since the inner function has access to the scope of the outer function, the variables and functions defined in the outer function will live longer than the duration of the outer function execution, assuming the inner function manages to survive beyond the life of the outer function.

// The outer function defines a variable called "name"

const pet = function (name) {

const getName = function () {

// The inner function has access to the "name" variable of the outer function

return name;

};

return getName; // Return the inner function, thereby exposing it to outer scopes

};

const myPet = pet("Vivie");

console.log(myPet()); // "Vivie"

An object containing methods for manipulating the inner variables of the outer function can be returned:

const createPet = function (name) { // the name variable is accessible to the inner functions

let sex;

const pet = {

// setName(newName) is equivalent to setName: function (newName)

// in this context

setName(newName) {

name = newName; // The inner variables of the inner functions act as safe stores for the outer arguments and variables, and are "persistent" and "encapsulated"

},

getName() {

return name;

},

getSex() {

return sex;

},

setSex(newSex) {

if (

typeof newSex === "string" &&

(newSex.toLowerCase() === "male" || newSex.toLowerCase() === "female")

) {

sex = newSex;

}

},

};

return pet;

};

const pet = createPet("Vivie"); console.log(pet.getName()); // Vivie

pet.setName("Oliver"); pet.setSex("male"); console.log(pet.getSex()); // male console.log(pet.getName()); // Oliver

Closures and Classes

When a closure returns an object, it can function as an alternative to a class.

- the key-value pairs of the closure correspond to the properties and methods of the class

Notice that the following closure can be implemented as a class:

const UserClosure = ({ firstName, lastName, age, occupation }) => {

return ({

describeSelf: () => {

const msg = `My name is ${firstName} ${lastName}, I am ${age} years old and I work as a ${occupation}`

return msg

},

getAge: () => {

return age;

},

showStrength: () => {

let howOld = age;

let output = 'I am';

while (howOld-- > 0) {

output += ' very';

}

return output + ' Strong';

}

})

}

Closures and classes behave differently in JavaScript with a fundamental difference: closures support encapsulation, while JavaScript classes don’t support it.

- in other words, we can create a closure where individual members of the closure are invisible to the outside world.

When opting for closures over classes, closures offer simplicity, since we don’t have to worry about the context that this is referring to.

- If we are creating multiple instances of an object, classes will best suit our needs. Meanwhile, if we don’t plan to create multiple instances, the simplicity of closures may be a better fit for our project.

Simple state-management with closure

function makeState<S>() {

let state: S

function getState() {

return state

}

function setState(x: S) {

state = x

}

return { getState, setState }

}

const { getState, setState } = makeState()

setState(1)

console.log(getState()); // 1

setState(2)

console.log(getState()); // 2

Observe that you can pass a type like so:

makeState<number>()

Then, when you go to use getState and setState, the generic S will become number

Inner/Outer function illustration

From the context of an inner scope, there is a: local scope, any number of closure scopes, and a global scope. The closure scopes represent the different scopes of the surrounding code. If our current scope is nested 3 levels deep then there are 2 closure scopes. Within these scopes, there may exist variables.

because of how lexical scope works, when we call a function that accesses a variable from outside its scope, it will capture it at the very time the function is created. This means even if that value changes in the future, the value it had at the time it was captured will be used.

var outer = () => () => {}

var innerFunc = outer()

- above,

innerFunccausesouter()to execute, returning a function and setting its value to it.innerFunchas access to the local variables of its containing object (normally a containing function). Therefore, these "sibling" local variables are changeable from outside the function. - Think of a closure as the lifeline that an inner function extends to the variables (that the inner function has used) defined in the outer function. They continue to exist because the closure exists. In other words, the inner function closes over (ie. captures/remembers) the variables defined in the outer function.

- Conceptually (but not actually), the closed over function (

outer) has all of its variables put into an object. That is howinneris able to access those values. Something like this is happening:

function outer() {

var x = 1;

return function inner(){

return x;

};

}

makes 2 objects like this:

scopeOfOuter = {

x: 1

}

scopeOfInner = {};

then scopeOfOuter is set as the prototype of scopeOfInner, so when we try to access the value of x with return scopeOfInner.x, we see that scopeOfInner doesn't have an x property, so it goes up the prototype chain and finds an x property on scopeOfOuter

Object.setPrototypeOf( scopeOfInner, scopeOfOuter );

- Conceptually, the structure of a closure is not mutable. In other words, you can never add to or remove state from a closure

- closures are a subset of lambdas

How scope enables closures to happen

In JS, a scope is created by a function or code block.

- When we have 2 separate functions at the same level of the code, both can use the same variable names and not have collisions. But what happens when one fn (

inner) goes within another (outer)?

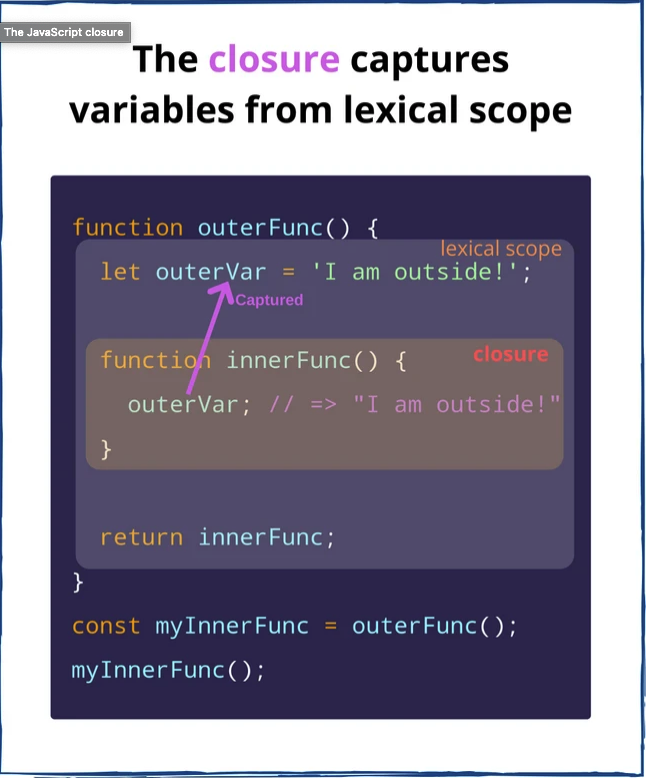

In the following example, myInnerFunc is an instance of innerFunc, with the enhanced benefit of having access to outerVar

- The reason it has access is because of lexical scope, which (importantly) is defined before any javascript code has run (ie. analyzed just by the source code)

- Therefore, a closure is a function that has access to its lexical scope, even though that function was executed from outside of that lexical scope.

- Simpler, the closure is a function that remembers the variables from the place where it is defined (and not where it was executed)

- A rule of thumb to identify a closure: if you see in a function an alien variable (not defined inside the function), most likely that function is a closure because the alien variable is captured.

Analogy

Imagine a magical paintbrush with an interesting property. If you paint with it some objects from real life, then the painting becomes a window you can interact with.

Through this window, you can move the painted objects with your hands.

Moreover, you can carry the magical painting anywhere, even far from the place where you’ve painted the objects. From there, through the magical painting as a window, you can still move the objects with your hands.

The magical painting is a closure, while the painted objects are the lexical scope.

Stale closures

- stale closures capture variables that have outdated values.

function createIncrement(i) {

let value = 0;

function increment() {

value += i;

console.log(value);

const message = `Current value is ${value}`;

return function logValue() {

console.log(message);

};

}

return increment;

}

const inc = createIncrement(1);

const log1 = inc(); // logs 1

const log2 = inc(); // logs 2

const log3 = inc(); // logs 3

log1(); // logs "Current value is 1"

log2(); // logs "Current value is 2"

log3(); // logs "Current value is 3"

log{1,2,3}()are stale closures, because it has already captured the value at the time thatinc()was called. What's important to note here is thatinc()is called 3 times. Every time it is called, it runs through theincrementfunction that was closed over. It then returns that value, and holds it (within a function calledlogValuethat prints out the held value). In other words, it does not get updated with each subsequent call ofinc(). It has already held onto that value, and there is nothing it can do to change that fact.- Therefore, if we want to capture the freshest value, we have to figure out which closure it is that has those freshest variables.

- Here, that variable would be the latest call of

inc().

- Here, that variable would be the latest call of

Closures vs Objects

closure offers granular change control and automatic privacy. object offers easier cloning of state

Closures are made every time we create an event handler, a promise, setTimeout, and even within useEffect in React.

Node Debugger

closure scope is outside of local scope there are multiple layers of closure state

Backlinks