Git Plumbing

"Plumbing" refers to the analogy of a bathroom fixture, where there is a porcelain part and a plumbing part. The Porcelain part is what we interact with on a daily basis, and the plumbing part is what happens under the hood.

Git was initially designed as a toolkit for a version control system rather than a full user-friendly VCS. These low-level commands were designed to be chained together UNIX-style or called from scripts.

How git data is stored

Git's database is built on references. It has models of commits, trees, blobs.

Essentially, it is just one giant acyclic graph

- here, acyclic means that we can pick one commit and traverse its parents in one direction and there will never be a chain that begins and ends with the same commit; no cycle of commits can be formed.

Commits are snapshots, not diffs

- Git takes snapshots (via commits), and stores it in something of a mini-filesystem. When Git stores a new version of a project, it stores a new tree (a bunch of blobs and a collection of pointers) that can be used to expand back out into the whole directory of files and directories.

- ex. if we change a single line in a single file, that is technically a new version of the project. However, Git is smart and it realizes that there were no changes in 99.9% of the files in the codebase. This "new version" of the project does in fact have its own tree, but because all (except one) of the blobs in this tree are just references to other blobs, this version of the project is extremely lightweight (in fact the only "weight" is the content of the new file). This way of handling snapshots is a core reason why Git is so efficient, yet so powerful.

Each time we create a file and begin tracking it, git compresses it and stores it into its own structure

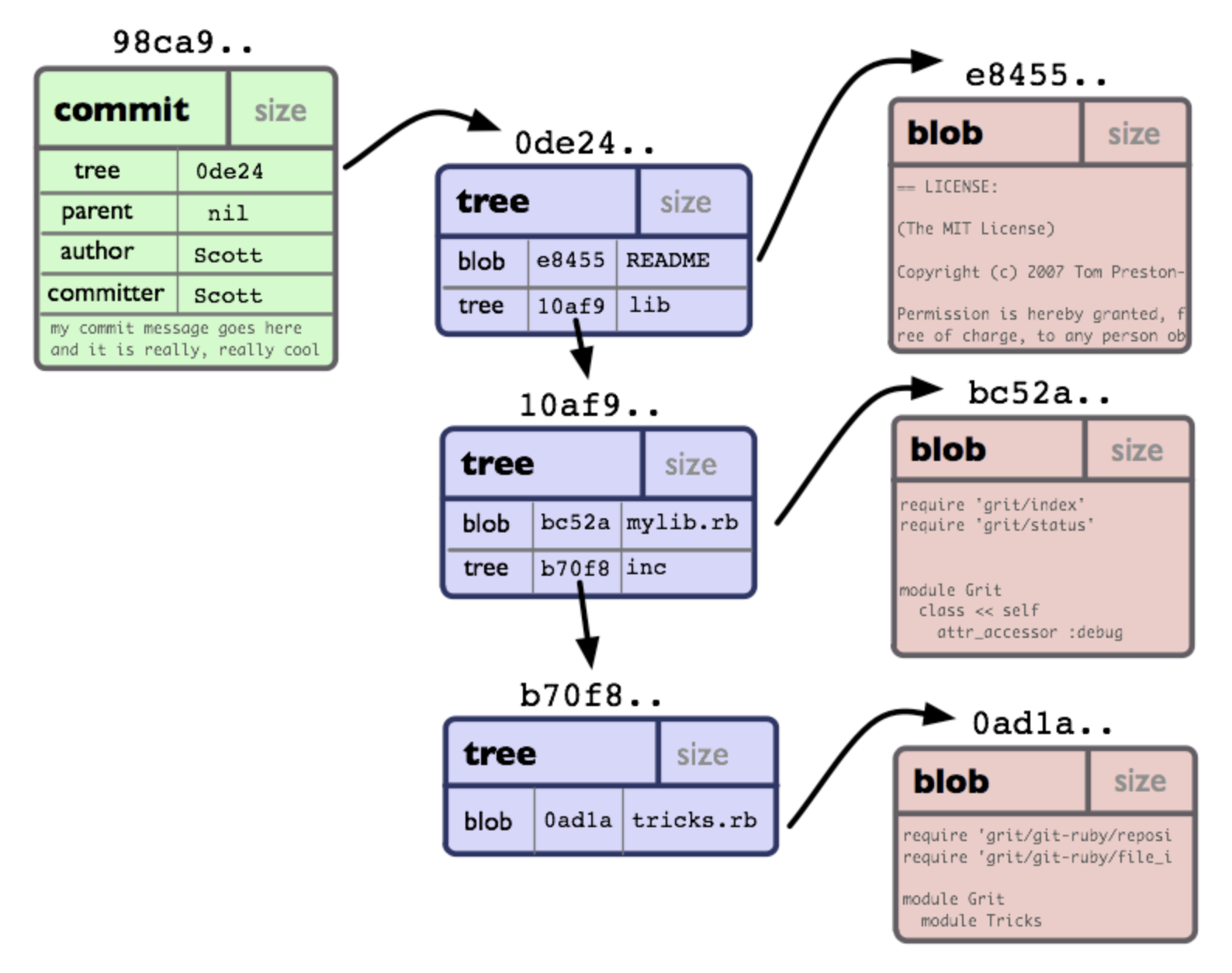

Git stores content similar to how a UNIX filesystem does. All content is stored as tree and blob objects

- trees would correspond to directories

- Like UNIX filesystem, all a directory is is a file with its contents listed. (The relationship between parent-child is made via reference, not the child actually being inside parent)

- blobs would correspond to file contents or inodes

A single tree object contains one or more entries, which is a SHA of a sub-tree or blob (ie. directory or file)

- ex. imagine we had the following project structure:

.

|-- README

`-- lib

|-- inc

| `-- tricks.rb

`-- mylib.rb

- if we made a commit, we would create a tree object for each directory, and a blob object for each file. It would be represented like this:

The reason we can represent the history of the codebase as a tree is because each snapshot (commit) specifies its parent

The object database is content-addressable, meaning that we can retrieve the data based on its content, rather than its location.

- This is a major reason why Git is so performant

At the core of Git is a simple key-value store, with the value being the content, and the key being a SHA representing that content.

Demo

- With a fresh git repo, upon adding

foo.txtto the index, a new object (in.git/objects) is created. If we rungit cat-fileon that object, we will see the contents of the file. - Upon committing, 2 more objects will be created:

- a tree object, which makes reference to

foo.txt, which points to a blob object SHA- if we

git cat-filethat SHA, we will see the contents offoo.txt.- What this demonstrates is that we have a tree object which references a filename, which is associated with the content in the file. None of these things are glued together, but they merely make references to each other.

- if we

- a commit object, with reference to the tree (the same tree that was just created)

- when we run

git commit, the SHA of that commit object is output into the console

- when we run

- We have just demonstrated that a commit points to a tree, and a tree points to a blob. First a blob is created (when adding to index), then committing will create a commit and tree object.

- a tree object, which makes reference to

- Now with a clean tree, we create a new file

bar.txt, and edit the contents offoo.txt. We add both those files to the index.- two more blob objects are created

- With those 2 files in the staging area, we commit, and 2 more objects are created: a tree object and a commit object.

- Since this is the second commit, it also references its parent commit

- The tree object will reference both

foo.txtandbar.txt

- Again with a clean tree, we create a new file

baz.txt, add it and commit it.- Interestingly, the tree object that just got created will reference all

foo,barandbaz, even though onlybazwas changed in this commit.- This is because the commit object maintains the entire state of every file (and every version of the file) by SHA at that point in time.

- This is precisely why we can cherry pick a commit and put it on disk

- This is because the commit object maintains the entire state of every file (and every version of the file) by SHA at that point in time.

- Interestingly, the tree object that just got created will reference all

How Git handles renaming files

There is no data structure in Git that stores a record that a file was renamed during a commit. Instead, Git attempts to detect renames during the dynamic diff calculation.

- There are 2 stages to this rename detection

- exact renames— here, OIDs (of the blobs) are identical, meaning that the contents of the files are the same; just with a different name.

- edit-rename— here, Git must iterate through each added file and compare it against each deleted file. From there, Git calculates a similarity score as a percentage of lines in common (anything >50% counts as a potential edit-rename).

After computing the diff, Git inspects it to discover which paths were added/deleted

- naturally, a file moved from directory

A/to directoryB/would appear as a file being deleted inA/and a file being added inB/. Git attempts to match these deletions/additions to create a set of inferred renames. - The first

What about if we rename a file then change some content in it?

- Git will track these changes as first a rename, then a modification to that renamed file.

Children