PubSub Pattern

Overview

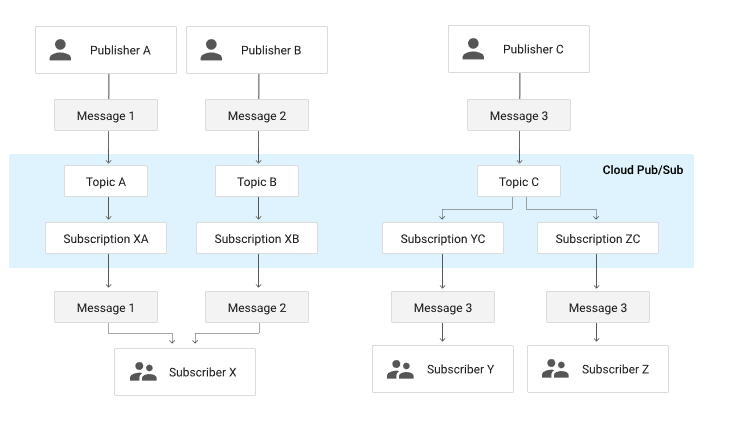

- stands for Publish-Subscribe senders (publishers) are not programmed to send their messages to specific receivers (subscribers). Rather, published messages are characterized into channels, without knowledge of what (if any) subscribers there may be. Subscribers express interest in one or more channels, and only receive messages that are of interest, without knowledge of what (if any) publishers there are. This decoupling of publishers and subscribers can allow for greater scalability and a more dynamic network topology.

Pub-Sub is a paradigm for getting real-time updates to a client. It is unlike webhooks, which would require the publisher of information to explicitly call someone who has "signed up" to receive it. Instead, with Pub-Sub the publisher determines that there is a certain set of information that it wants to send out, and it specifies a container (the topic) that it will be sent to. This leaves the topic open to be subscribed to, which a subscriber (a client) may do. The subscriber specifies that it is interested in receiving any new messages that arrive in a specific Topic (by name), and when new messages arrive, they are sent to the client.

- This topic name would be scoped for a specific user, for instance we might call it

graphql:user:${userId}

A common example of pub-sub are push notifications on mobile devices, since information preferences are expressed in advance by the user.

- A client "subscribes" to various information "channels" provided by a server; whenever new content is available on one of those channels, the server pushes that information out to the client.

A subscriber receives messages either by Pub/Sub pushing them to the subscriber's chosen endpoint, or by the subscriber pulling them from the service. Upon successful receiving of the message, the subscriber informs that it was received successfully.

Pub-sub is a messaging pattern whereby senders of messages (publishers) do not program the messages to be sent to the receivers (subscribers). Instead, the publishers categorize published messages into classes, without knowing who the subscribers are that will ultimately consume those messages

- Similarly, subscribers express interest in one or more classes and only receive messages that are of interest to them (without any knowledge about who the publishers are)

- This above explanation shows that the Pub-Sub paradigm results in the publisher service and the subscriber service being decoupled from one another.

An RSS feed might be a good analogy for the Pub-Sub paradigm, if we consider that we don't really care where each post/article came from. We just get them all lumped together, and consume them there, without any real consideration to where they came from. The process is decoupled.

Communication may be:

- 1:many (fan-out)

- or, many clients subscribing to one topic (ie. multiple subscriptions to 1 topic)

- ex. Twitter,whereby one single tweet is sent to all the parties following the person sending the tweet.

- many:1 (fan-in)

- or, one client subscribing to many topics (ie. multiple subscriptions to multiple topics)

- many:many

The pub-sub pattern provides greater network scalability and a more dynamic network topology, with a resulting decreased flexibility to modify the publisher and the structure of the published data.

Different pub-sub systems have different trade-offs, and when determining which system to use it's often worth asking the questions:

- What happens if the producers send messages faster than the consumers can process them?

- Broadly speaking, there are three options:

- the system can drop messages,

- buffer messages in a queue,

- If messages are buffered in a queue, it is important to understand what happens as that queue grows. Does the system crash if the queue no longer fits in memory, or does it write messages to disk? If so, how does the disk access affect the performance of the messaging system

- apply backpressure (also known as flow control; i.e., blocking the producer from sending more messages).

- ex. Unix pipes and TCP use backpressure: they have a small fixed-size buffer, and if it fills up, the sender is blocked until the recipient takes data out of the buffer.

- Broadly speaking, there are three options:

- What happens if nodes crash or temporarily go offline? Are any messages lost?

- As with databases, durability may require some combination of writing to disk and/or replication, which has a cost. If you can afford to sometimes lose messages, you can probably get higher throughput and lower latency on the same hardware.

Core concepts

Topic

- messages are sent to resources, which we call Topics or Streams.

- topics have names that uniquely identify them

- ex. if we are subscribing to the event "user clicks this button", then the topic might be named

user-clicks-CTA

- ex. if we are subscribing to the event "user clicks this button", then the topic might be named

- the topics live on a server controlled by the publisher

- ex. Postgraphile server, Google Pub/Sub

- a topic can be defined as a group of partitions that all carry messages of the same type.

Subscription

- A subscription represents the stream of messages from a single specific topic.

Relation to Message Queue paradigm

the Pub-Sub paradigm is a sibling of the "Message Queue" paradigm.

- Most messaging systems support both the Sub-Pub and Messaging Queue paradigms in their API.

Relation to Job Queues

Job Queues only let one "subscriber" watch for new "events" at a time, and keep a queue of unprocessed events.

- ex. Celery

It turns out that Postgres generally supersedes job servers as well. You can have your workers "watch" the "new events" channel and try to claim a job whenever a new one is pushed. As a bonus, Postgres lets other services watch the status of the events with no added complexity.

Examples

- Kafka

- RabbitMQ

- NATS

- Redis PUB/SUB

Backlinks